When a Silver Bullet Backfires: Analyzing the Effectiveness of Microcredit

A fundamental challenge to international development is the poverty cycle ingrained in the world’s poorest nations. In what’s known as “the development trap,” efforts to improve quality of life and spur economic growth through foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and multilateral agencies often see little or negative results.

Setting the stage

Microcredit loans began gaining traction in the 1990s, attempting to address this widespread poverty. Proposed by Professor Muhammed Yunus’ Comilla Model at the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, microcredit describes the establishment of a large network of small-scale lending as a means to provide small loans to vulnerable citizens without requiring collateral. This is intended to improve the financial stability and quality of life of the borrowers, and in turn, that of their communities. In principle, these loans are to be provided at a low interest rate, guaranteeing some profit for the lender while prioritizing the impoverished borrower. This promotes a social incentive for borrowers to take out loans, while also mitigating risk to lenders by spreading the cost over many borrowers. For several decades, microcredit was widely regarded as “a silver bullet” for poverty reduction, with Yunus being awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for his model in 2006. However, in practice, the long-term impacts of microcredit to relieve poverty have been limited.

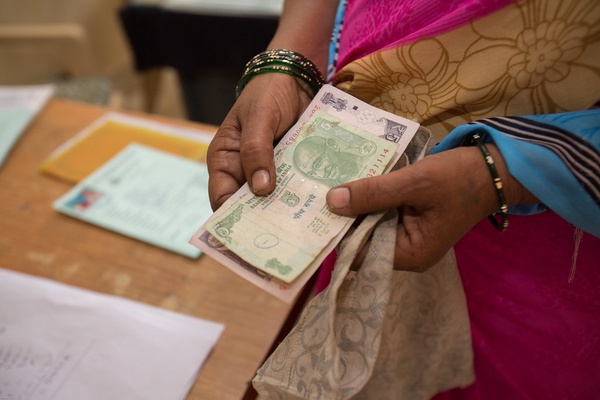

Uplifting the status of women

These initiatives are targeted primarily towards women and providing them with the capital necessary to create small businesses and new employment opportunities for their communities. Providing money to women has been shown to yield greater investment in their education and health while empowering them to achieve independence. It is well documented that as women acquire capital, they spend more of their income on their households than do men, making a more positive impact on their family and the local economy. Interestingly, the push to provide micro-loans to women was largely inspired by the spread of feminism and the resulting promotion of women in the workforce in the 1970s.

When money is put into the hands of women, they also enjoy an increase in household decision-making roles, from budgeting, to sending their children to school, to family planning. According to the Women’s Opportunity Fund, a group of Balinese widows received loans and started an enterprise raising pigs, eventually expanding into a major pig-feed cooperative supplying food for their village. Another client in Ghana reported:

“He [her husband] gives me more value since the loan. I know, because now he hands all his earnings to me [….] Before, my husband used to beat me when I asked him for money. Now, even if he doesn’t earn enough every day, I can work, we don’t have to suffer.”

This progress also spurred greater macroeconomic benefits. The redistribution of wealth through micro-loans led to an increase in the average wage in these communities, as small-scale entrepreneurs were able to expand and hire other locals. However, this growth was limited, as many unskilled entrepreneurs eventually found themselves in immense debt and with few prospects to repay the loans. Firms exacerbated these barriers by raising interest rates which, in turn, drove down demand for labour and any other hope for business expansion. Gradually, the idealization of microcredit diminished.

The dark side of microcredit

In theory, the microcredit model seemed ideal for reducing poverty, at least according to the UN, which declared 2005 the “International Year of Microcredit.” Despite praise in its early years, in 2012 several whistleblowers who had formerly worked in the micro-financing industry emerged. They exposed unethical behaviour, which included excessive interest rates, poor client screening, and general incompetence by employees. As firms colluded to raise interest rates on loans, the profits for lenders climbed and the benefit to borrowers diminished. With this exposure came the downfall of the micro-loan, as it became clear that firms prioritized profit over the prospects of vulnerable borrowers.

By the end of the 2000s, the positive reputation of micro-finance loans within the international development community began to fade as the harmful impacts for borrowers and their communities became evident. In an op-ed for the New York Times, Yunus, who had initially created his model to provide an alternative to “loan-sharks,” criticized the shift away from non-profit banks and towards “programs seeking to profit from the suffering of the poor.” At the root of this problem was over-lending, which left many unskilled entrepreneurs burdened with significant debt. With high-interest rates and rigid loan repayment schedules, loaners were ensured short-term profitability while exploiting impoverished borrowers. In 2010, this became so extreme that the government of the Indian state of Hyderabad was forced to issue an order shutting down all microcredit institutions nationally; business owners who had used microcredit experienced mass debt and violent pressure to repay their loans, and more than 200 suicides by borrowers were reported.

The ethical backing for loans as a development strategy has disappeared, as small-scale entrepreneurs are effectively subsidizing the more affluent, larger clients of these lending firms. Given the emergence of this startling debt trap for the world’s most vulnerable, it is clear that the current structure of microcredit is ineffective.

The future of development

The good news is that changes in implementation strategies can be made. For these changes to be positive, development agencies will need to promote the involvement of local individuals in their solutions. Burman University anthropologist Adam Kiš posits that “culture eats strategy for lunch,” suggesting the need to understand the historical traditions and social dynamics that have determined the ways populations live. Impoverished people must be allowed a voice and stake in their development process. Loan allocation, interest rates, and repayment plans must be rethought to better serve the borrower and the community in which they are targeting; one-size fits all foreign intervention has been seen to fail more often than not.

Notable economists like Jeffrey Sachs and Rohini Pande have presented alternatives for economic development, including cost-free savings accounts and increased access to digital financial services. In practice, removing the fees associated with opening a savings account in Kenya led to an increase in the number of clients, their overall savings, and market investment levels. In terms of digital finance services, traditional economic theory suggests that the full potential of markets can only be realized when participants have full access to information to make rational decisions. Digital programs promote this through faster information and service for clients, even in remote areas. Addressing these considerations would achieve greater long-term market and developmental yields.

Relieving poverty worldwide is imperative to achieving the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. In its current state, microcredit is inefficient and often counterproductive to long-term progress in developing countries. Looking to the future, we must revise the techniques endorsed by NGOs and multilateral agencies such as World Vision and the United Nations, prioritizing the prosperity of borrowers over profit for lenders. For the sake of development, the microcredit model must be restructured to fulfil its intended purpose.

Featured image: “Taking out a microfinance loan” by waterdotorg is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Edited by Emily Jones