When Planting Gets Political: Urban gardening for social reform — PART I

PART I: Combatting a Global Food Crisis

In cities across the world, groups of people from all walks of life are changing the face of urban living for the better. Their strategy of choice is deceivingly simple: getting their hands in the dirt to garden.

In recent decades, urban gardening has notably risen in the ranks from an eclectic (and, admittedly, geriatric-seeming) hobby to the focus of numerous academic investigations. These shifts have not occurred under subtle circumstances—rooted in a range of motivations, from a desire to grow fresh produce amidst sprawling food deserts, to resisting urban decay from government mismanagement, or donning a fresh appearance to drab concrete streets, these green enclaves offer strategic opportunities to invest in our communities on multiple fronts.

This short series will explore the interconnected benefits of urban gardening, shining the spotlight on the power of planting to nurture the longevity of cities and the wellbeing of their inhabitants. Perhaps, in engaging with local initiatives like these gardens, we may find unexpected solutions to broader global crises and generational afflictions.

PART I: Combatting a Global Food Crisis

Food security is a seemingly straightforward goal at face value. At the bare minimum, to consider someone ‘food secure’ is when they have the “physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs.” Yet amidst a range of pressures–including inflation and human-induced climate change—we are falling deeper into what the World Bank has described as a “global food crisis” threatening food security for millions. According to their most recent report, approximately 80.4 per cent of high-income countries are experiencing unprecedented hikes in the price of food. Floods, droughts, fires, and other destructive natural disasters caused by climate change have placed immense stress on global food production capacities, a condition that has been compounded by the damaging use of pesticides and fertilizers that degrade fertile soil. All of the above has acted to inhibit affordable access to daily sustenance, much less a healthy diet.

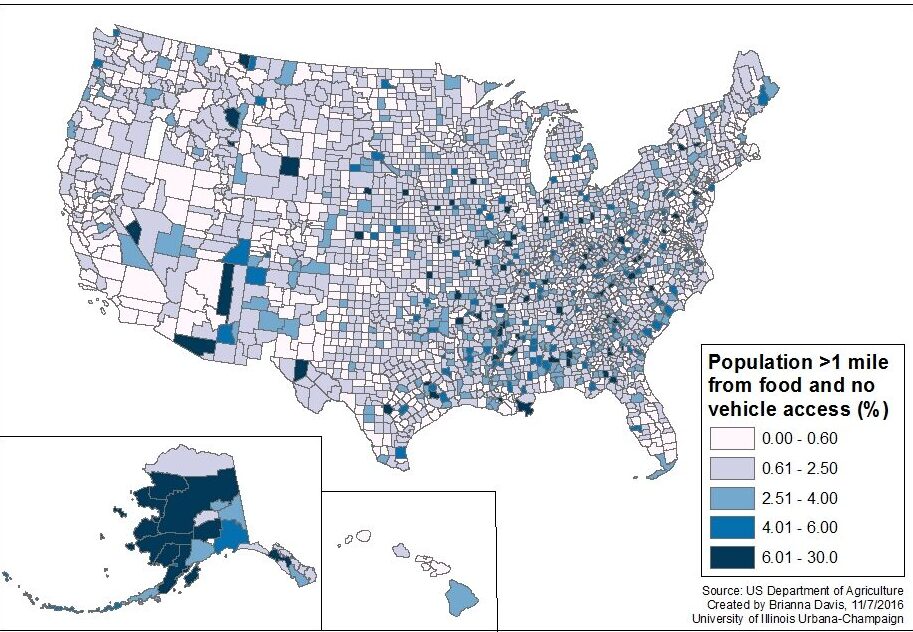

Urban areas play a central role in the discourse surrounding food insecurity. Urbanization is a process that is only predicted to continue in the coming years, with an estimated 68 per cent of the global population to be living in cities within just a few decades. Along with the expansion of these cities and their populations comes a destructive erosion of arable land and more people living farther away from where their food is grown. As consumers rely on the transport of crops from distant farms to their urban locales, their extended food supply lines are vulnerable to shocks or disturbances, with potentially devastating consequences for human security. To give just one example, if global food supply lines were to be cut off, a study found that existing food stores and food production capabilities in Stockholm would last only two weeks before the city’s inhabitants faced threats of starvation. This plot thickens when considering the lower-income urban neighborhoods facing so-called ‘food deserts.’ These deserts, broadly characterized by a lack of affordable and healthy food—particularly fresh produce—may arise from an outright absence of grocery stores in a given area, or otherwise a lack of affordable transportation to food sources, likewise threatening inhabitants’ food security.

City populations are not only physically distant from their food sources; growing up with limited access to nature or environmental activities, younger urban generations may face an imminent loss of agricultural knowledge. Some researchers have argued that a “global generational amnesia” on how to grow food is already occurring as “spaces and skills related to local food and water management rapidly vanish on a grand scale” and residents lack practical, on-the-ground understanding of plant life. Others have gone as far as to claim a widespread “cognitive disconnect” from nature in cities, where individuals are removed from experiences displaying humans’ deep-rooted dependence on the natural world.

Amidst this bleakly anticipated future, can widespread gardening truly generate global change? Community gardeners argue that, yes, while urban gardening is certainly not a be-all-end-all solution to such a vast issue, it is a potent tool that can both offset food scarcity and overcome detachment from the natural world.

Using urban and community gardens to combat food shortages is not a particularly novel idea. In 18th-century Europe, rapidly industrializing nations faced mass rural-to-urban migration, and garden plots were allotted to the poorest of urban masses to combat resulting food shortages. During both World Wars, relief or ‘Victory Gardens’ were established and encouraged by governments in order to alleviate hunger; England’s World War I campaign was particularly notorious for its takeover of parks, sports fields, and even parts of Buckingham Palace to combat war-time shortages, successfully producing two million tons of vegetables in 1918. More recent examples include Cuba, where gardens in Havana sprung up following trade blockades, Barcelona and Greece in the aftermath of the 2007-08 financial crisis, and multiple cities throughout China. Researchers today have certainly caught on to the success of these past tactics and have arrived at a common conclusion investigating gardens around the world: urban gardens are indeed “conducive to increasing urban food production” and an opportunity to reassess food security.

Perhaps even more significant than their edible produce is the potential of gardens to reconnect urban inhabitants with their natural environment. From their inception, community gardens are inherently teaching spaces, relying on the knowledge of individuals to be shared and its participants to be taught so the gardens can be constructed and ultimately thrive. As they develop, gardens congregate individuals from diverse backgrounds and age groups who exchange techniques, information on plants and wildlife, and knowledge of local climates. The intergenerational character of these exchanges is particularly important—children learn where their food comes from and can inherit experiences from older citizens that, if not passed along, could vanish altogether. And the physical practice of planting and growing is itself a means of hands-on learning, fostering a deep appreciation for ecology and human dependence on the natural world.

The reconnection with nature that gardening offers is not simply a nostalgic yearning reserved for outdoors aficionados or environmental activists — it is critical to our future. A comprehension of and expertise with nature is what informs not only basic food production but, arguably, any hopes for innovative problem-solving against food scarcity. It is especially crucial for children and young people to be exposed to the environment when considering how (or if) they will advocate for it in the future; without direct experiences of the joy, tranquillity, or straight-up fun that can be found when immersed in the natural world, whether it be hiking around wild forests and lakes or simply spending time in cities’ green enclaves, it is hard to imagine what will inspire the next generation of environmentalists.

Hence, not only have urban gardens been historically depended on during food shortages, holding timely potential in the face of our current global food crisis—their role in remedying alienation from nature is key to enacting a more sustainable human existence, one plot at a time.

Edited By Lily Molesky

Featured Image: “Evergreen Community Garden” by Matt Green is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.