Where East Meets West – Montenegro’s Pledge to Europe

On the 16th of October, Montenegro held its second parliamentary election since independence from Serbia in 2006. Political pundits from London to Moscow labeled these elections as a historical moment in the country’s path. The contest pit the pro-western Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), whose leader Milo Djukanović has run the country since the 1990s, againstthe blatantly pro-Russia coalition Democratic Front (DF).

Europe’s longest elected leader, Djukanović, has faced “historical, path defining, and decisive” elections before, among which was a gamble for independence in 2006. Time and time again pundits have predicted his fall, and each time they have found themselves biting their tongues.

As in most transitioning states, corruption and nepotism are often insurmountable obstacles. The case is no different for Djukanović’s 26-year reign. Yet, despite rampant allegations Montenegro’s ‘Milo’ has managed to cling to power in spite of a century-old societal cleavage.

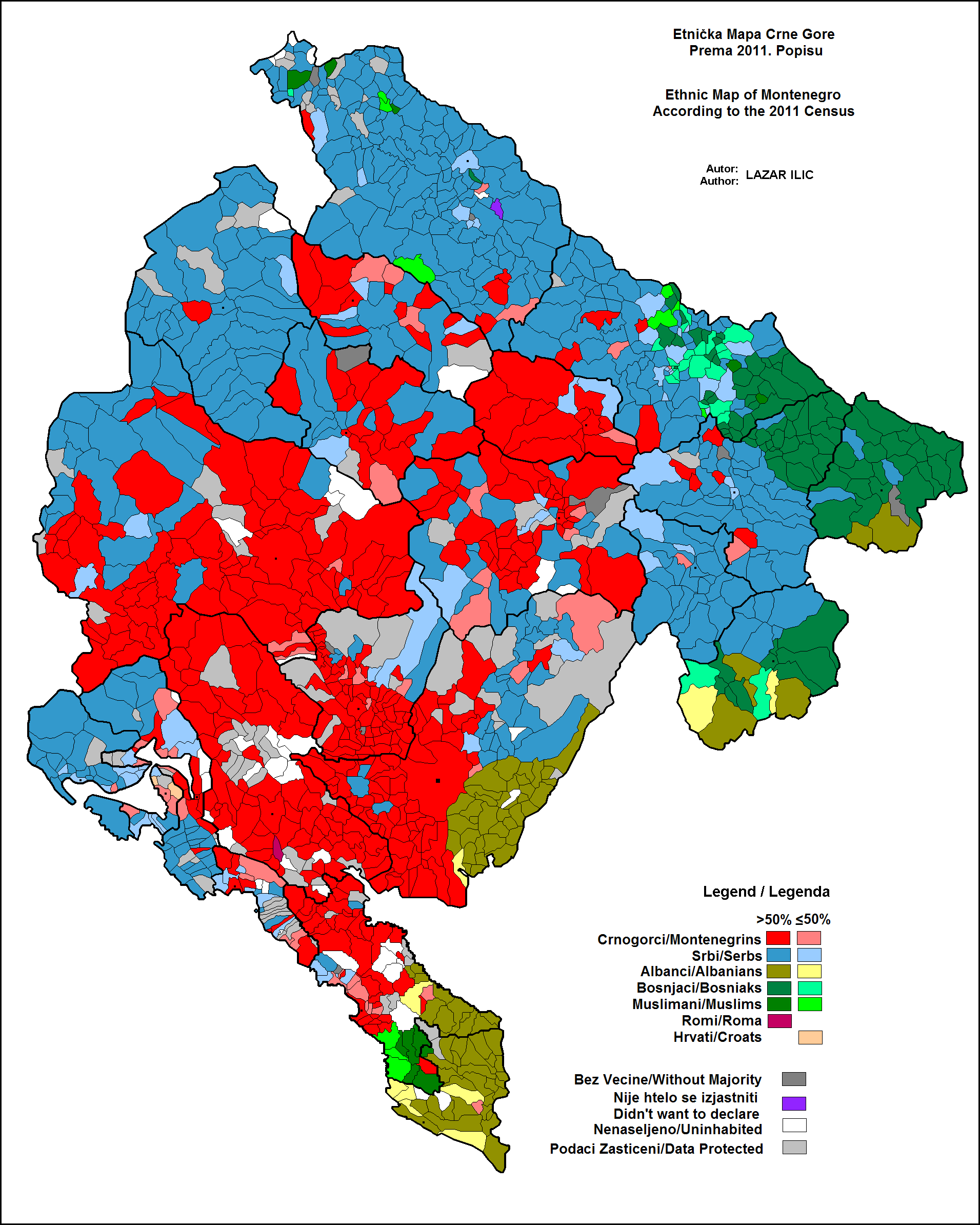

The cleavage centres on the question of the existence of a unique Montenegrin people and language that had been suppressed and even banned for years under Serbian rule. The divide runs deep, as ethnic Montenegrins comprise roughly 45% of the population; however, only 36% declare Montenegrin to be their mother tongue. Serbian on the other hand is spoken by over 43%, despite ethnic Serbs making up 28% of the country. As a result, one’s political allegiance is closely tied to ethnic identity. With the incorporation of Montenegro into Serbia with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1918, the general pro-Serb policy has been that Montenegrins are a regional declination of Serbs. Censuses dating back to the early 20th century show the emergence of a Montenegrin ethnicity in 1948, and prior to that many declared themselves as Serbs or simply as Orthodox. However, as a state Montenegro existed independently for nearly a century prior to unification with the Kingdom of Serbia. The fact that several prominent Serbian figures such as Slobodan Milošević, Radovan Karadžić, the Karadjordjević dynasty, and so on hail from the mountains of Montenegro adds to Serbian claims on the lands to the Adriatic.

It is this fact, as absurd as it may sound, that has enabled Milo to be in power for so many years. For the “Anti-Montenegrins” he is an enemy just as much as to “Pro-Montenegrins” he is the sole guarantor of hard-earned statehood. Today this cleavage has grown from arguments over linguistics and bloodlines to discourse on where the state’s strategic allegiance lies. Generally speaking the country is split into those who see themselves as members of the Montenegrin camp (this includes the three historical minorities: Albanians, Bosnian Muslims, and Croats) and the Serb camp. The former tends to support Djukanović’s Euro-Atlantic path; the latter, led by the DF, a warming of relations with the East.

Violent protests erupted countrywide as DF supporters and others targeted public institutions following Montenegro’s invitation to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization last December. At the height of the tensions, the DF-backed protests turned Montenegro’s quaint Adriatic squares into scenes resembling Kiev’s Euromaidan. At the time, Prime Minister Djukanović warned of Russia’s increasing grasp in domestic affairs as information leaked that protestors were receiving financial and logistical support from Moscow. Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov naturally denied such allegations, but proceeded to warn against accession to NATO and the European Union.

It is estimated that this was one of the most expensive election campaigns conducted in Montenegrin history. In addition to money from the federal budget, Parties collected three times as much money from donations than in all previous elections. The Prosecutor’s Office in Podgorica has began investigating indications of illegal donations made from abroad with a particular focus on donations from Russian sources.

In light of these events, what would seem to many to be another Parliamentary election became a quasi-referendum on whether the public continued to support Montenegro’s path towards Euro-Atlantic integration or wanted for a return to traditional Eastern partnerships with Russia and Serbia.

The voters (more than half a million had registered) chose 81 deputies on 17 electoral lists. Once again Milo’s DPS defied the experts, winning 42% or a total of 36 seats, for a 5 seat increase from previous elections. In addition, the pro-European coalition Ključ surprised observers by securing 9 seats in its first election run. As for the eastward-oriented DF, it ended up with 18 as opposed to the 20 seats they had previously held. The end of the intense contest allowed the people of Europe’s second youngest state to breathe. In a post-electoral press conference, the returning President could not help decry how “great powers conspired against small Montenegro. It was not easy”, adding that Montenegro continues down the path of European security and integration. While Montenegrins have made their stances clear, those in the neighbourhood have had a hard time adjusting to the new political era.

The morning of the elections, Montenegrin police arrested 20 citizens of Serbia on charges of “planning terrorist attacks on civilian targets, disturbing the peace and planning to kidnap Montenegrin Prime Minister Milo Djukanović and his family”. Until further notice, the Prosecutor’s Office suspects that the criminal group planned to assault citizens and police in front of the Montenegrin Parliament, and then to occupy the premises of the Assembly, with a declaration of victory for “certain political parties”. Prosecutor General Milivoje Katnić believes other members of the group are yet to apprehended, stating that police found the terrorists in possession of Montenegrin Special Police uniforms. As a result, Katnić said, there is evidence the group intended to make the attack resemble a coup. Among those arrested was former commander of the Gendarmerie of the Serbian Interior Ministry, pensioner Bratislav Bata Dikić, also know as ‘Little Legion’. Dikić retired from service in December of 2015 after being tied to several executions committed by officers under his command. Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić distanced himself from Dikić, who “presents his disapproval for the Government of Serbia on a daily basis”, but was also quick to refute allegations, claiming that he would “like to see and hear real information that he was planning a terrorist act. I would like it if these men were not arrested on the word of an (ethnic) Albanian police officer, but unfortunately I have information that this was the case”.

Whether or not Belgrade and or Moscow are directly involved will remain within the cables of embassies around the region. However, it is clear that an invisible hand from somewhere has been meddling in Montenegrin affairs, and the people have finally had enough of being told what language they speak, whose blood runs in their veins, and to whom their country should pledge loyalty. Barring a miracle, Montenegro is destined to become a full pledged member of NATO by the summer of 2017 and complete the requirements of EU accession by 2019. The merits of Djukanović’s nepotism and corrupt ways are enough for several opinion pieces on their own. Nonetheless, he has defied all odds in wrestling his country away from the jaws of the East and into a new era of peace and cooperation with Western partners. His name shall be printed into the textbooks of generations to come for one reason or another, but one is for sure: Djukanović and those who vote in his favour will be remembered for their historical defiance.

The featured image by Ggia is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.