Could Banning Nuclear Weapons Threaten World Peace?

In 1917, McGill University physicist Ernest Rutherford made history when he became the first person ever to split the atom. By severing nature’s smallest unit, Rutherford unleashed what would become nature’s greatest force: nuclear energy. Quickly, scientists found that nuclear fission — the chain reaction set off by splitting nuclei — could be used to make weapons with unprecedented capacities for killing. Fearing that this force might fall into the hands of Adolf Hitler, a Jewish refugee named Albert Einstein sent a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt in 1939 explaining the new and precarious technology that was the nuclear bomb.

“Pa,” muttered Roosevelt to General Edwin “Pa” Watson, his secretary, as he read the letter, “Pa! This requires action!”

Action ensued. With the initiation of the Manhattan Project, and a few tests in a New Mexico desert, the first nuclear bombs were ready to drop, not thirty years after Rutherford’s experiment. And on August 6th, 1945, “a flash of light and a wall of fire destroyed a city” — as President Obama described it while visiting Hiroshima in 2016 — “and demonstrated that mankind possessed the means to destroy itself.”

75 years after the first instance of nuclear warfare, the safety — and quite possibly the existence — of life on Earth remains dependent on the lack of a second. Aware of this, the UN has spent much of its lifespan forging multilateral agreements in attempts to avoid atomic Armageddon. But on October 24th, 2020, the international community reached a landmark treaty that triumphs over all predecessors on nuclear containment: the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Under this pact, nuclear weapons are, for the first time in history, illegal under international law for the 50 states that ratified it.

Signed by 122 countries in 2017, the TPNW then needed to be ratified by 50 in order for it to become a legally-binding document. On October 24th, Honduras became the 50th ratifier. The treaty will come into effect on January 22nd, 2021, banning the development, possession, and use of nuclear weapons for those 50 countries. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres described the treaty as “a meaningful commitment towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons, which is the highest disarmament priority of the United Nations.”

Though widely appraised, the TPNW will have little to no effect in eliminating any of the 13,000 nuclear warheads scattered across the globe today, since none of the world’s nine nuclear arms-possessing countries have ratified the document. Most allies of the “big nine,” including Canada and the rest of NATO, followed suit.

However, members of the nuclear club will no longer be able to use the territories of TPNW signatories for the strategic placement of nuclear weapons. Furthermore, the TPNW will serve as a key mechanism in proliferation prevention. In this sense, the treaty is a more modern and ambitious cousin of the 1968 Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), which did not explicitly outlaw nuclear weapons. According to Daryl Kimball, Executive Director of the Arms Control Association, the TPNW will also set an international norm that such weapons of mass destruction “are immoral, dangerous, and unsustainable.”

The ratification of the TPNW is a testament to the growing role of civil society in international politics. A coalition of NGOs known as the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) rigorously lobbied states to sign the TPNW in 2017; an effort which won it that year’s Nobel Peace Prize. Civil society groups like ICAN could be the key to countering the nuclear club’s dominance in the UN — an often criticized feature of the body — by circumventing constraints faced by member states, like alliances and strategic interests.

On the world stage, Canada is often associated with peace. It was Canadian Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson who, in an effort to pacify belligerents during the Suez Crisis, invented the United Nations Peacekeeping enterprise.

So why did Canada not sign the TPNW?

Despite their unpopularity among the general public, nuclear weapons actually have a pacifying effect on the world, particularly between major powers.

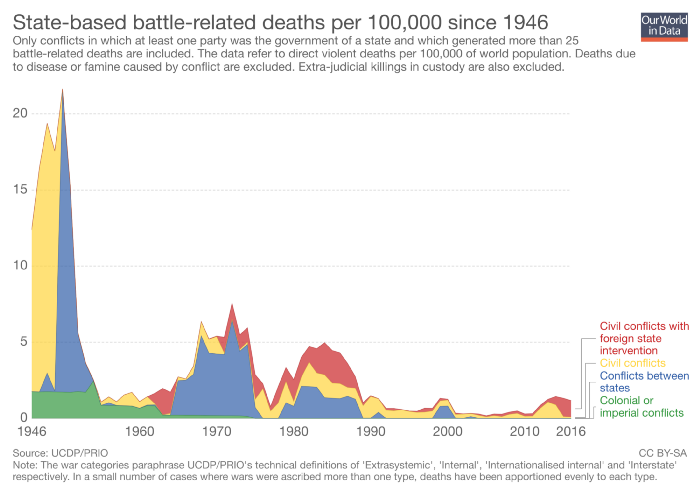

Since Hiroshima, the world has experienced no trans-continental wars, no conventional warfare between the international systems’ strongest powers, and human loss-of-life as a result of war has dropped astronomically. Quite counterintuitively, these trends suggest that such weapons of mass destruction serve as sturdy defenders of world peace. It follows then that the total elimination of nuclear weapons, which according to Antonio Guterres is a UN priority, would undermine the state of relative world peace that has existed since the end of WWII.

Among adherents of nuclear peace theory is NATO, of which Canada is a member. NATO’s nuclear doctrine holds that nuclear arms serve as deterrents to security threats, because they threaten consequences to potential attackers which could never be rationally accepted.

Nuclear weapons also curb tensions between global superpowers. From the Peloponnesian to the World Wars, war between the international systems’ strongest players was once just a fact of life — a fact which consistently produced immense casualties around the world. Today, the threat of mutually assured nuclear destruction looms over tensions between superpowers, “trigger[ing] fear, which in turn makes leaders cautious,” according to Sciences Po professor Benoit Pelopidas.

Consequently, nuclear weapons have drastically decreased interstate violence, as evidenced by the International Crisis Behaviour dataset. After all, not one bullet was ever fired between American and Soviet soldiers as they competed for global hegemony, despite their engagement in one of the most hostile rivalries in modern history.

In fact, a brief 1999 dispute between Indian and Pakistani forces in the town of Kargil, part of the contested Kashmir region, is the only instance in history in which two nuclear states have engaged in a direct war. “Though some form of limited military conflict between [nuclear] rivals is a distinct possibility,” says King’s College London professor Simon Moody, “the risks of a costly and unrestricted conventional conflict has largely been nullified by the presence of nuclear armouries.”

Despite their deterrent and pacifying effects, nuclear weapons do not come absent of dangers. There is always the possibility of accidental detonations. In 1961, two nuclear weapons fell out of a US military plane over Goldsboro, North Carolina, but did not detonate simply because the safety switches stayed in position.

Furthermore, nuclear deterrence relies on human rationality, which becomes a gamble if such weapons proliferate into shakier hands. As NATO’s official deterrence policy highlights, “a modern, democratic state actor will not be able to judge what a terrorist group, such as Daesh, deems ‘cost,’ ‘benefit’ or ‘unacceptable damage.’” It was for this reason that the international community was so adamant about stopping Iran’s nuclear pursuits. A radicalized body itself, Iran’s theo-autocratic government has also been identified by the US State Department as a sponsor of several terrorist organizations in the Middle East. Though President Obama spearheaded a multilateral agreement that ended Iran’s uranium-enrichment program, his successor’s scrapping of the Iran nuclear deal has allowed these programs to resume.

Finally, nuclear peace only applies to possessors. While the decrease in hegemonic conflict has done wonders for overall world peace, conflict between dominant states sometimes finds a new home in proxy settings. Take the Vietnam War, for instance. Proxy conflict can exacerbate violence within non-nuclear countries, which tends to disproportionately affect people in the developing world.

Coordinated international efforts, like the TPNW, will be necessary in combating the imperfections of nuclear peace. However, the total banning of nuclear weapons would reverse the trend of decreasing warfare between the world’s major powers, and in turn, increase violence across the globe. In the words of Winston Churchill: “It may well be that we shall by a process of sublime irony have reached a stage in this story where safety will be the sturdy child of terror, and survival the twin brother of annihilation.”

Featured image: “Anti-nuclear demonstration in front of Japanese PM residence” by Matthias Lambrecht, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Edited by Jacob Lokash