Why isn’t China getting younger?

In 1979, Chinese Leader Deng Xiaoping instituted the famous “one-child policy” to control the booming Chinese population. Struggling with severe food and housing shortages, the Chinese faithfully welcomed the change. However, it had a lasting impact on the Chinese economy decades later that no one predicted. The one-child policy may have slowed China’s population growth, but it fundamentally skewed the social structure of China’s population today. 40 years later, China must deal with the consequences—the imminent aging Chinese population.

Since the launch of the one-child policy, birth rates have steadily declined. Strict government commitment to reducing population growth through forced abortion, sterilization, and financial penalties all sped up the process. However, things soon turned sour. As a rule of thumb, the fertility rate required to maintain a stable population growth in the long run is 2.1 and China is far below that level at 1.6. Up until 2016, each woman was allowed one child – consistent with a fertility rate of 1. Low fertility rates imply a smaller future population entering the workforce, and hence a higher dependency ratio—a ratio measuring the size of the working population relative to the population that is under 14 years of age and above 65. As China experienced the steepest population growth between 1949 to 1979, this entire generation will soon be retiring.

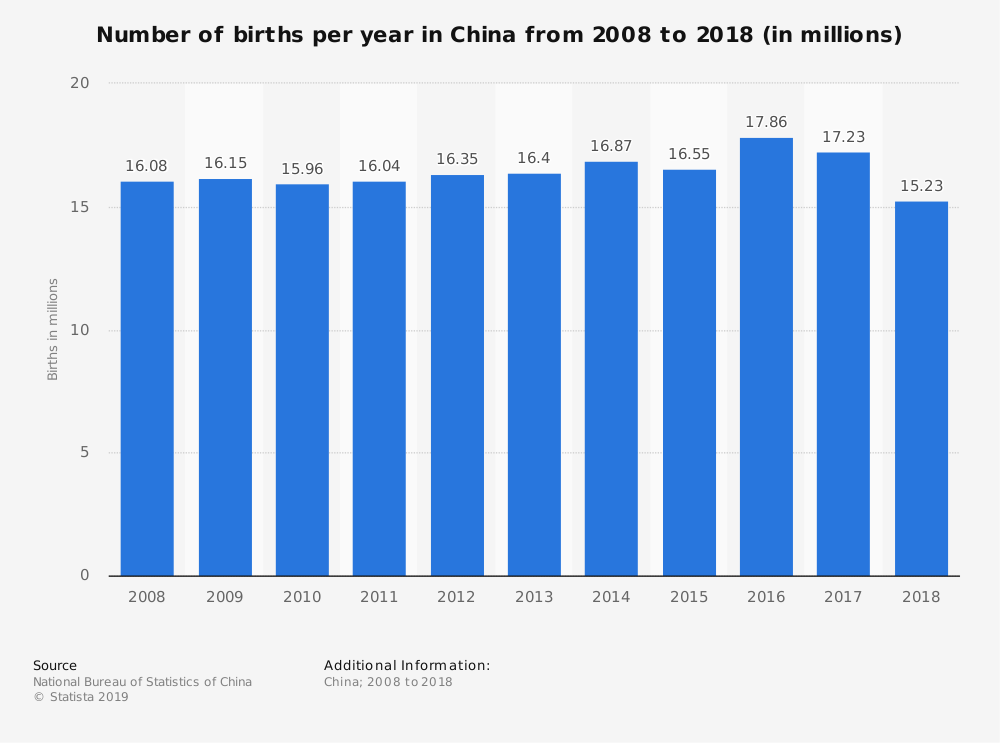

Without a reasonably-sized working population to support the elderly, China is in for economic trouble. An aging demographic demands increased pension fund investment, which puts pressure on the Chinese economy as will the country’s shrinking workforce. According to Beijing’s National Academy of Economic Strategy, pension shortfall could reach $130 billion by 2020. The issue is that China cannot afford to spend more with an estimated current level of debt sitting at 3 times its GDP. Recognizing the implications of an undersupported aging population, the Chinese government scrapped the old policy in 2016 and introduced the “two-child policy.” The new policy correlated with a jump in birth rate by 7.9% from 2015 to 2016, but fell by 3.5% the following year and by 11.6% in 2018. What in theory should have boosted population growth failed in practice. Why is the policy not working?

The one-child policy has played a critical role in shaping the social and cultural values adopted by Chinese people today. Raised as only children respectively, young married couples have grown comfortable with the idea having a single child. The policy has also instilled in them an “only-me” mentality which prioritizes career achievements over family, thus delaying marriages. Discrimination by employers who find it costly to pay for maternity leave further discourages women from having a second child. Finally, the Chinese culture to favor male births over female births has resulted in a distorted gender ratio. By 2020, an estimated 24 million men will be unable to find wives. Then, even those who are willing and able to support a larger family will be barred from contributing to China’s future labour pool.

Social and cultural changes alone do not explain the general reluctance to having more children. Young couples are limited by financial resources. Education, health care, and housing costs in China are simply too high for an average family to afford more children, especially in urban areas. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences reported in 2015 that the average cost of raising a child from birth to 16 years old is 139 percent of the country’s per capita total disposable income over that same period. As more recent statistics are not yet available, this figure does not reflect today’s true cost of raising a child, however it is likely quite similar. In addition, having a second child means taking resources away from the existing child and allocating them to the newborn, which many are unwilling to do.

The strongest deterrent is the phenomenon of the inverted “4-2-1 pyramid.” As a result of the one-child policy, a young person today is weighted by the burden of supporting a mother and father who will soon reach retirement, and 4 grandparents given the rising life expectancy. Receiving another member into the family adds to the current load which itself it an immense responsibility. The reality is that an individual’s financial position determines whether or not to raise a child.

Clearly, the two-child policy is not achieving its goals and alternative actions must be taken. The Chinese government has initiated tax breaks in addition to education and housing subsidies. Other incentives come in the form of marriage compensations, loosened abortion policies, and extended maternity leave to beyond 98 days (just under three and-a-half months). The government is also experimenting with propaganda. Last year, stamps for the year of the monkey presented two baby monkeys in agreement with the two-child policy. The recent release of a stamp with three piglets in 2019 hints at the possibility of a three-child policy.

However, the projected effectiveness and impact of the incentives are questionable. For example, longer maternity leave makes employers more hesitant to hire women. Monetary compensation also comes at the expense of forgone opportunities for other sectors. One particular difficulty lies in the government’s aim to target higher birth rates among educated women, who are often career-driven and and live in urban areas where the cost of living is substantial. A starting point might be enforcing anti-discrimination laws against employed women. Monetary incentives and propaganda have their appeals and shortfalls. The question is—are there better alternatives?

Today, China faces the consequences of a decision made 40 years ago. The country is poorly prepared for the incoming aging population, and the cost of the elderly will be borne by the next generation of workers. The two-child policy, personal incentives, and pension fund investments are set in preparation for the demographic change. However, to overcome the hurdle, the government must address the root of the problem and understand why birth rates are falling. Overcoming the hurdle is a collective effort and the government must invite the participation and support of each individual.

Edited by Nathan Lautens