Women in War: The Rise of Gendered Violence in Venezuela

Machismo. Noun. A strong sense of masculine pride: an exaggerated masculinity.

This term has been tied to Spanish and Portuguese societies for years as a defining factor in gender relations, often to negative effects. Feminists such as Leonore Adler have stated that “machismo as a cultural factor is substantially associated with crime, violence, and lawlessness independently of the structural control variables”. Additionally, doctors such as Rosina Cianelli have additionally attributed the failure to implement HIV prevention programs and the prevalence of rape in rural societies to machismo ingrained into Latin American societies. As wide ranges of officials have disparaged this construct, it is evident why it must be discussed; and this is even more paramount in the context of Venezuela. Why?: Due to the statelessness the country is in.

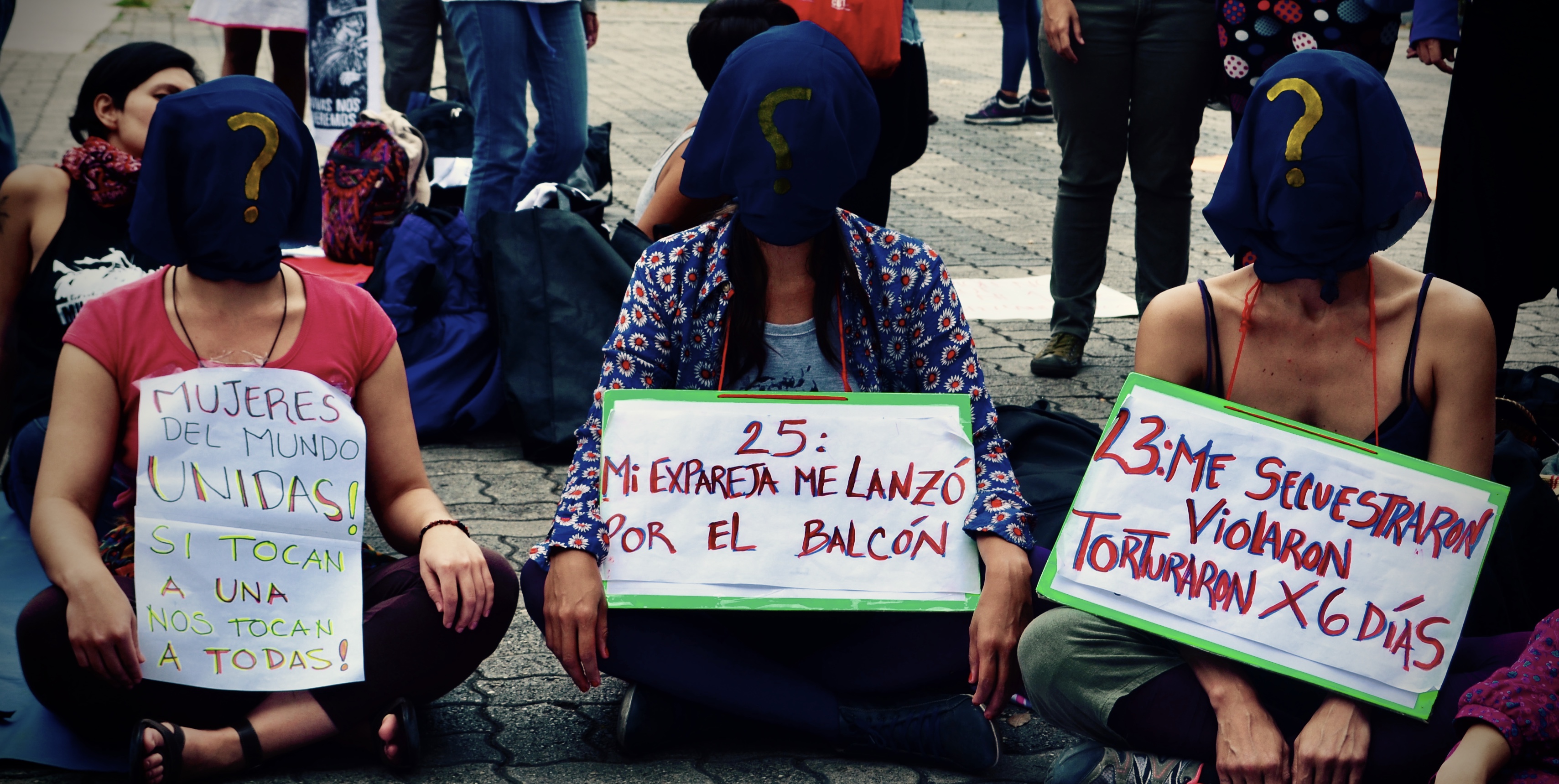

Luz Patricia Mejía, a lawyer at the Organization of the American States (OAS), has argued that violence against women is on the rise due to the absence of the Venezuelan state. Her assumption makes sense: with state funding down, police and military services diverted to rebels, and the justice system in shambles, violence can clearly proliferate. With reports stating that sexual and domestic violence is disproportionately placed upon women, it seems that the statelessness present in Venezuela streamlines gendered violence even more.

One main instance of this is the rise of the Venezuelan human trafficking trade, both in regards to forced labour and sexual slavery. There seems to be two reasons for this: the government and the economy. On the political end, besides the clear complacency of the state’s police forces, there is a linear correlation between public corruption and human trafficking as proven by the United Nations’ Office on Drug and Crime. For instance, it is alleged by the United States Embassy that a number of border patrol offices at the Venezuelan border have been payed off to ignore human traffickers shipping slaves out of the country to international hotbeds of slavery. With Venezuela ranking 166 out of 176 nations on the Corruptions Perception Index, it is apparent that this nexus between human traffickers and public officials won’t be curved until this corruption is addressed.

Economically, the rise of human trafficking is even darker. Many women, looking at a severely depleted job market, have turned to sex trades to subsist. However, as an unregulated, underground industry, this has made women increasingly vulnerable to sexual slavery. Additionally, as the Venezuelan bolivar has become useless, the sex trade has become a commodity exported by Venezuela. For instance, statistics state that there are a whopping 4500 Venezuelan sex workers in Colombia, and while they may be making more substantial money with the stable Colombian peso, it is reported by ASMUBULI, a Colombian sex workers association, that sex workers in foreign nations are at a much higher rate of human trafficking than those in their home country. Stories of women being trapped by the smugglers who brought them into Colombia and women being withheld pay for their services are sadly the norm, not cautious fables.

This all is not to say that the Maduro government is not trying at all; it is just to say that their attempts, for the most part, are weak. For instance, while Maduro has increased monthly subsidy payments to pregnant Venezuelan women from $700,000 to $1,000,000 bolivars, this increase, in reality, is the equivalent of increasing payments from $3.83 to $5.48, a measly amount of money to subsist on especially when pregnancy costs are accounted for.

More recently, President Maduro has declared himself a “feminist” and has stated that, alongside the Venezuelan Ministry for Women and Gender Equality, he will “ensure that not a single woman loses access to her rights, today and tomorrow”. The aforementioned Ministry for Women and Gender Equality, for instance, has recently passed a bill entitled the Humanized Childbirth Plan, which proposes shelters tone-built for impoverished pregnant women, medical training for doctors who oversee childbirth, and the building of pre-birthing shelters. While sounding nice, however, the Humanized Childbirth Plan seems to be more dreamt of than reality, as state funds are already scarce and funneled into the military, leading many to believe that this was merely an act for goodwill rather than a legitimate plan.

Overall, this is not to say that Venezuela did not have these problems before the devolution of the Maduro state. Nor is it to say that these issues don’t also affect men in large numbers, as they do. However, under the war-like nature of the state, issues such as rape, domestic abuse, and human trafficking are falling disproportionately on women and need to be addressed. This has to be done in more effective ways than giving women two extra dollars or implementing thinly veiled promises of a better ‘future’ with no concrete definition of what that future is. Maduro cannot expect systemic change until he has a three-pronged solution: dealing with corruption, poverty, and sexism. While daunting, however, all is not lost. The United States, for instance, made significant efforts to decrease human trafficking in 2017, and if one nation can do it, so can Venezuela.

Edited by Benjamin Aloi